Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire

1/27/2026 | 1h 23m 55sVideo has Audio Description

Learn about Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author of Night.

Learn about Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author of Night. After his internment at the Auschwitz Concentration Camp and liberation from Buchenwald, Wiesel became a journalist in France before immigrating to America. Over the course of his life, Wiesel fought the “sin of indifference” by writing, teaching, speaking truth to power and championing for human rights.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Support for American Masters is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, AARP, Rosalind P. Walter Foundation, Judith and Burton Resnick, Blanche and Hayward Cirker Charitable Lead Annuity Trust, Koo...

Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire

1/27/2026 | 1h 23m 55sVideo has Audio Description

Learn about Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author of Night. After his internment at the Auschwitz Concentration Camp and liberation from Buchenwald, Wiesel became a journalist in France before immigrating to America. Over the course of his life, Wiesel fought the “sin of indifference” by writing, teaching, speaking truth to power and championing for human rights.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Masters

American Masters is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

A front row seat to the creative process

How do today’s masters create their art? Each episode an artist reveals how they brought their creative work to life. Hear from artists across disciplines, like actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt, singer-songwriter Jewel, author Min Jin Lee, and more on our podcast "American Masters: Creative Spark."Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪♪ ♪♪ [ Wind whistling ] [ Fire crackling ] ♪♪ [ Wind whistling ] -Elie spent most of his life looking for the shadows, seeking out the darkness... in the hope that he could do something about it.

-Last night I saw my mother in a dream.

She seemed upset and I realized that something serious had happened.

She motioned me to follow her.

Then suddenly I saw my father.

He was wearing my gray suit.

It looked good on him.

♪♪ We were all there.

Everyone from before and from now.

Standing at a river that, all at once, began to swell.

[ Water rushing ] Its level rising from moment to moment.

"It's the flood," someone said quite calmly.

"It's the flood, but I am not afraid."

Just then my father waded into the murky blood-colored water, and I said to myself, "So rivers of blood exist after all."

He stayed beneath the water.

I began to shout for help.

But everyone was suddenly gone.

I don't know how to swim, so I panicked, screaming louder and louder, but I was all alone.

And I found him.

I don't know what power aided me.

All I know is that I managed to save him all by myself.

I helped him stretch out on the grass, listened to his breathing.

In my dream, he was alive.

My mother too... in my dream.

Whether we want it or not, we are still living in the era of the Holocaust.

The language is the language of the Holocaust.

The fears are linked to it.

The perspectives, unfortunately, are tied to it.

-The first time we met, I asked Elie, "What do you actually do?"

And he answered me with a smile.

He said, "I'm a storyteller, a teller of tales."

[ Feedback squealing ] -The first tale I always tell comes from the darkest hour of my generation.

I was young, almost a child, when I saw it unfold before my eyes.

Somewhere in the Kingdom of the Holocaust, 1944.

♪♪ ♪♪ In my small town, somewhere in the Carpathian mountains, I knew where I was.

I knew why I was born.

I knew why I existed.

Now I no longer know anything.

As in a dusty mirror, I look at my childhood and I wonder if it is mine.

In Sighet, my town, Shabbat began on Friday afternoon.

Shops closed well before sundown.

After the ritual bath, my father would walk to services, dressed for the occasion.

Sometimes my father would take my hand as though to protect me, as we passed the nearby police station or the central prison on the main square.

I liked it when he did that, and I like to remember it now.

The merchants conducted their businesses.

The students studied Talmud.

The beggars wandered from house to house to get a bit of food for Shabbat to their families.

Life was normal.

I would give so much to be able to relive a Shabbat in my small town.

The whiteness of the tablecloth, the blinking candle flames, beaming faces around me, the melodious voice of my grandfather inviting the angels of the Sabbath to accompany him to our home.

It is this Shabbat that I miss.

-The old feeling of religious Jewish family celebrating Shabbat.

To Elie, Shabbat is the ultimate thing.

Shabbat is... It's what is home.

What it -- what it meant to him.

-[ Speaking French ] -I come from a very religious background, very religious family.

My dream was to become a teacher of Talmud.

We Jews in Hungary, in our ghetto, we didn't know about Auschwitz.

People tried to hang on to a fragment of hope in spite of logic.

They said to one another, "It's inconceivable, after all, that the Hungarians would send us all away.

How could a town go on functioning without its physicians and businessmen, without its watchmakers and tailors?

The town needs us.

Society needs us."

No one among us, and surely not I, still young to possess the sense of reality could imagine that there will come a day darker than others, when we, too, will be going towards the unknown.

In 1944, very quickly things happened.

Between Passover and Shavuot.

For several weeks, the ghetto was created.

Transports began and the entire city from 12,000 to 15,000 Jews were sent to Auschwitz.

I left my native town in the spring of 1944.

It was a beautiful day.

The surrounding mountains and their green light seemed taller than usual.

Our neighbors were out strolling in their shirtsleeves.

Some turned their heads away.

Others sneered.

At times I tell myself that I have never really left a place where I was born.

In my study over the table where I work, there hangs a single photograph.

It shows my parents' home in Syria.

When I look up, that is what I see and it seems to be telling me, "Don't forget where you came from."

[ Train wheels screeching ] The name meant nothing to us.

[ Women screaming ] Immediately separated us from my mother and my sisters.

I remained with my father.

Everything was so fast.

And then something strange happened to me.

When I saw these hundreds and hundreds and thousands of Jews coming from all over Europe, speaking all languages, belonging to all cultures, to all conditions, I had the feeling this is a messianic event.

The Messiah is coming.

To claim was not a messiah but death as Messiah.

♪♪ ♪♪ -[ Speaking French ] -[ Speaking French ] -Auschwitz was the name of a little railroad station.

Even inside Auschwitz, they did not believe that Auschwitz was something else than a little railroad station.

But Auschwitz became a center of Jewish history.

Oh, yes.

At that point, and at that period, Jewish history ran through Auschwitz and not through New York or London or Stockholm.

But you know that.

I'm sure that many people went to their death not even believing afterwards that they were dead.

[ Wind whistling ] Everything died in Auschwitz.

Ideals died there.

Men died there.

The idea of God, the image of God changed, underwent a horrifying metamorphosis there.

It was my father who kept me alive.

We saw it together.

And I wanted him to live.

I knew that if I die, he would die.

And we arrived to Buchenwald.

There were hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people in one barrack.

My father got sick -- diarrhea.

And one night... I heard him call me.

And that morning, he died.

And I felt he wanted to tell me something, but I couldn't.

And again, even today, I tried to figure out what was his testament.

What did he want to tell me?

-The thing that personally touched him the most of being in a concentration camp was the fact that he couldn't help his father.

His father was dying and he asked him to come and help him, and he couldn't.

That was a deep, deep wound.

-One day, really, I saw myself in that mirror.

And I saw a person who was ageless, nameless, faceless, a person who belonged to another world, the world of the dead.

One of the things that every survivor has to face and does face today is the fact of its own survival.

He somehow is ashamed of still being here and not part of the others who are no longer here.

In that place of eternal darkness and silence, we live not only with the dead.

We lived in death.

♪♪ I belonged to a group called the Buchenwald Children.

We were 400 children in Buchenwald.

Then the American army liberated the camp.

The youngest was 8, 7 or 8.

The oldest was 18 or 19.

I was 16.

Then France offered us refuge.

That train ride, which lasted a few days, was very special.

We received from the American Army, I remember, cookies, and the first thing we did, we shared our cookies.

♪♪ When we arrived, they separated us in two groups -- those who were religious and the others.

I had outbursts of anger, of despair, too.

But the moment we came to France, in that children's home, I became a religious.

Those homes were very, very special.

And I remember the songs with great, great affection and tenderness and melancholy and nostalgia.

-And that was the beginning of the surrogate families ahead of the big, um, bonds of friendship that's more than friendship.

That's really like brothers, more than brothers that you still see so today.

-We didn't cry.

Maybe because people were afraid if they were to start crying, they would never end.

Our problem was how to adjust to death.

It was normal to go to sleep with corpses and wake up with corpses, wondering whether you are not one of them.

After the war, it was difficult once more to see in death a scandal, to see in death once more a source of pain.

One day, there were journalists who came to do a story about our... After all, children from Buchenwald was a good story.

I played chess with a friend.

They took pictures.

Alright.

[ Camera shutter clicks ] And then later, I was in the office of the director.

[ Telephone rings ] And I heard him speak on the telephone, mentioning my name.

I said, "I heard you mention my name."

He said, "Are you Elie Wiesel?"

I said, "Yes."

He said, "I just spoke to your sister."

I said, "I don't believe it.

What do you mean?

Must be a mistake.

Even if she remained alive, what is she doing in France?

If she is in France, how does she know I am here?"

"But," he said, "But she has a message for you.

She will wait for you tomorrow at the railway station in Paris."

I didn't sleep all night, as you can imagine.

Then came next day, and there she was.

♪♪ Hilda simply saw my picture in the paper.

She had met a Algerian Jew in the DP camp immediately after the war, and she followed him to marry him in Paris.

-[ Speaking French ] I left the children's home.

I went to Paris.

I cut myself off from the city and from life for weeks on end.

I lived in a room which was much more like a prison cell, large enough for only one.

I looked only at the Seine River bearing along its foam.

I no longer perceived the sky mirrored in it.

And I threw myself immediately into learning.

I was looking for myself.

I was fleeing from myself.

And always there was this taste of failure.

♪♪ -A friend went to visit Elie Wiesel, and he goes in to a small, little apartment and the room is pitch black and there's just a single candle burning.

There's classical music playing.

He's not saying anything.

My friend said, "He could tell that -- He knew I was there."

After a bit of time, he just turned around and left.

-I remember once asking him, "How can you write so fluently?"

And he said, "I get up at 4:00 in the morning.

I just sit in front of the white page and my hand goes to the pen and it starts writing."

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -The act of writing is, for me, often nothing more than the secret of conscious desire to carve words on a tombstone to the memory of all those I loved and who, before I could tell them I loved them, went away.

♪♪ -He had migraine headaches, terrible headaches.

The pain that this caused, the torment, the anguish.

-I drew away from people.

No tie, no liaison came to interrupt my solitude.

I lived only in books where my memory tried to rejoin a more immense and ordered memory.

And the more I remembered, the more I felt excluded and alone.

I had lost my faith in many things, and I had lost my sense of belonging and orientation.

And my faith in God was shaken.

I found myself living in the ghetto.

-He told me that he lived or spent a lot of time with the clochard, the homeless in Paris.

And he didn't open his mouth for almost a year.

And when he opened his mouth, he had French.

He had it.

-I remained with French because I acquired the French language in France.

And I needed a new language.

I needed it like a home, a new home.

-His French was fluent but not perfect.

But he did all of his writing in French all along, even though he really had only spent a few years in France, where he spent many more years in this country.

-I was sent by a French paper to Israel in '49 to cover the immigration from the DP camps, and I went there for a few months and came back to Paris, remained a foreign correspondent in Paris.

-I thought it was interesting that he was a reporter, because I thought maybe that was part of his way of dealing with it, that if you report on things, um, you sort of have to learn about them and then you're telling other people about them.

And -- And maybe that was a way back into reality.

♪♪ -Things have changed in the world, and perhaps the world itself has changed.

Have I?

♪♪ When I write, I have the feeling literally, physically, that my grandfather and my mother is looking over my shoulder and reading what I'm writing.

I want to be sure that the words will be the proper words.

At one point, I decided to write my testimony.

I had made a vow in '45 to wait 10 years.

I wanted my language to be the monument to our people, especially to those who died.

-How does one overcome trauma?

Well, he overcame it through becoming a witness.

"Night," of course, was the epicenter.

-He wrote the original book in Yiddish.

-It was published in Argentina.

My manuscript was 864 pages.

It was called "Un di velt hot geshvign," "The World Was Silent."

I wrote it for the other survivors who found it difficult to speak, and I wanted really to tell them, "Look, you must speak."

"10 years after Buchenwald, I see that the world forgets.

The German army has resurrected.

War criminals walked in the streets.

The past has been erased, forgotten.

Germans and anti-Semites tell the world that the story of the 6 million Jewish, that is only a legend.

And the naive will believe in it.

If not today, then tomorrow.

The world that was silent yesterday will remain silent tomorrow."

-The title of the Yiddish is pissed off at non-Jews.

It's the world kept silent.

This idea that -- that Jews feel unseen, their sorrows unappreciated.

And what we have in the Yiddish is the way Holocaust survivors talk.

-He wrote this for a very specific audience, but it was not written for those who did not read Yiddish or didn't have access to Jewish culture and Jewish languages to access that book.

-The French is poetic, symbolic.

It doesn't stick its finger in anybody's chest.

It points at a kind of cosmic catastrophe.

-This is the original copy that nobody wanted.

And it's all falling apart.

-In "Night," which was translated from the Yiddish and shortened because no publisher would have taken the full version.

In fact, they rejected even the shorter version.

-The book was published, did not, I think, get a lot of attention at first, but then, you know, had this extraordinary life.

"The night that -- that is described here still hangs over many parts of the world.

And no one, nor anything, can promise us that it won't threaten us tomorrow."

-He brings us to Auschwitz with him.

It is both this specific account of this boy's traumatic experience and it's, at the same time, this kind of eternal mythical account.

-"I witnessed hangings in the camp.

One day we saw three gallows rearing up in the assembly place, three victims in chains, and one of them, the little servant, the sad-eyed angel.

To hang a young boy in front of thousands of spectators was no light matter.

The head of the camp read the verdict.

All eyes were on the child.

The three victims mounted together on to the chairs.

The three necks were placed at the same moment between the nooses.

'Long live liberty!'

cried the two adults.

But the child was silent.

At a sign from the head of the camp, the three chairs tipped over.

Total silence throughout the camp.

The two adults were no longer alive, but the third rope was still moving.

Being so light, so light, the child was still alive.

For more than half an hour, he stayed there, struggling between life and death, dying in slow agony under our eyes.

And behind me, I heard, 'Where is God now?'

And I heard a voice within me answer him.

'He is hanging here on these gallows.'"

-"Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night.

Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust.

If I survived, it must be for some reason."

-History is vital.

You can't understand the Holocaust without knowing the history.

But you need more than the history.

You have to be able to imagine some of these things.

You will never know why -- And Elie said this early on, if you weren't there, you won't know.

You have to take students and readers further than that.

You have to help them to imagine what is it like, for example, to get up in the morning and you're starving.

And when you go to bed at night, you're still starving and knowing you're going to get up the next morning, you're also going to be starving.

And it may all end in you're being shot or sent to the gas chamber.

How do we help people to imagine what that must have been like?

-But even if you read all the books, all the documents by all the survivors, you would still not know.

Only those who were there know what it meant being there.

Why I write?

What else could I do?

I write to bear witness.

The more I remembered, the more I felt excluded and alone.

Whom was I to lean on?

I shunned love.

Aspiring only to silence.

Aspiring only to madness.

-Elle had a part of him that was very, very difficult to reach and very tough.

I thought he would never have children.

-The first time I met him was at my friend's.

This was at a dinner party in her house, and she was my closest friend.

And she said to me, "You're meeting Elie Wiesel.

I just want you to know he's a very interesting guy, but not somebody you would ever think of marrying."

After this dinner, we had one date and we both knew that it was going to be.

-Once he met Marion... a switch occurred.

She released in him the thirst to live a little bit more normally as a human being.

-What does a man dream when he is 40 years old and has made a decision consecrated by the law of Moses, to make a home with the woman he loves?

Custom dictates that before his wedding, an orphan go to meditate at the grave of his parents.

But this groom's parents, like millions of others, had no grave of their own.

All creation was their cemetery.

-He had told me from the beginning he didn't want children.

He said, "I don't want to bring a child into this world."

I convinced him.

When Elisha was born, Elie became more religious.

He had never stopped being religious.

He uncovered it.

It was like peeling off layers of non-religion and his true self emerged, which was religious.

-At this particular time, Elie did tremendous traveling.

He would leave Elisha notes, and he'd say, "I'm not here, but I will be back.

And tomorrow we shall celebrate again, my son."

I would say to myself, "I can't believe that he's leaving these notes to this, like, 3-year-old."

-When I see my son, I tell him stories, and I sing him tunes about tales to be told one day by him.

And then he smiles.

And his smile is not his alone.

His smile is my grandfather's who went to his death perhaps dancing and singing about my son.

-It wasn't easy for Elisha as he went through school.

Everywhere, he was Elie's son.

He didn't have a chance to be himself.

-It was very difficult to be a 6- or 7-year old, and you're out at the playground talking about what your parents do for a living.

And one kid is, "Oh, my dad, you know, he used to be in the Israeli Air Force.

And now he flies EL AL plane."

And the other kid is, "Oh, my dad's a pharmacy.

He gets medicine to help sick people."

And I'm like, "I think something really bad happened to my dad, and now he writes or talks about it."

It was very confusing.

How do you ground yourself and your parent's career around that?

I don't think I really processed "Night" until I traveled with my father to Sighet in 1995, with my cousin Steve.

My father almost... I saw him almost as a radio transmitter that could pick up frequencies that no one else was picking up.

And it's because he was picking up the ghosts and he made them real for us.

Even if he didn't talk about them, the way it weighed on him made it extremely real.

And it really was on that trip that I think it hit in a deep way for the first time, that the Nazis had killed a woman who should have grown up to be my aunt.

-The transformation in, I think, American Jewish awareness of Holocaust and the breakthrough of Elie's recognition came at the Six-Day War.

Everybody was convinced the Holocaust is about to occur again.

-With the success of the "Holocaust" TV show, suddenly you could teach the Holocaust in schools, right?

It could be part of the curriculum.

-Prior to the '70s, '80s, survivors were not encouraged to talk about what they endured.

And Elie was perhaps the first person to encourage them.

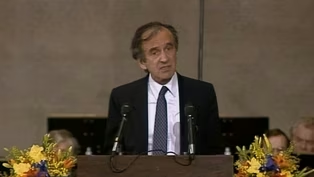

-No one has taught us more than Elie Wiesel.

His life is testimony that the human spirit endures and prevails.

Memory can fail us, for it can fade as the generations change.

But Elie Wiesel has helped make the memory of the Holocaust eternal.

Elie, we present you with this medal as an expression of our gratitude for your life's work.

[ Applause ] -Elie was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

What happened the week that Elie was going to receive the medal was the whole uproar about Bitburg.

Reagan was going to go to Germany for a state visit, and he was asked by President Kohl to visit a cemetery of German soldiers.

And it turns out that there were Waffen-SS soldiers buried in that cemetery.

And so this got a tremendous amount of publicity.

-The Holocaust must never be forgotten by any of us.

And in not forgetting it, we should make it clear that we're determined the Holocaust must never take place again.

I think that -- I think that it would be very hurtful, and all it would do is leave me looking as if I caved in in the face of some unfavorable attention.

I think that there's nothing wrong with visiting that cemetery where those young men are victims of Nazi-ism also.

Even though they were fighting in the German uniform, drafted into service to carry out the hateful wishes of -- of the Nazis, they were victims just as surely as the victims in the concentration camps.

And I feel that there's much to be gained from this and in strengthening our relationship with the German people who, believe me, live in constant penance -- All these who have come along in these later years for what their predecessors did and for which they are very ashamed.

-We were in a hotel room in Washington.

There for the event, and one of the other... Many of the important leaders of the Jewish organizations came to see Elie.

They came to the room in the hotel and they pleaded with Elie.

They didn't want him to go against the president's wishes, and they felt that it was better to... leave things unsaid.

-Do we have a... -We have about five minutes.

-Well, why don't we take some chairs over here?

-Where would you like to sit?

-Well, I think that we're all the victims right now of a lack of understanding.

And let me be clear what is taking place.

I'll have to say that I've always believed forgiveness is divine, but I don't think I'm ever going to be able to forgive the press for their handling of this, what they've done.

And I did not mean when I said they were victims, too, that their experience in any way was parallel to yours.

I simply meant that I think everyone who died in that war on all sides were victims of the Nazi terror, the horror that that man loosed on the world.

And as a matter of fact, he made a personal visit.

And as you know, the tombstones there are flush with the ground.

And it had snowed, and he, in good faith, said, "No, there are -- there are no SS in the cemetery."

-Well, I think it's safe to say that the president's remarks on his entire trip in Germany will draw a distinction between the German soldier and the SS, and that he will in no way condemn, I mean, approve or say any kind of approving word regarding SS, Nazis or the Third Reich.

-In order to diminish the publicity, the White House set the stage in a small room instead of the larger room, because they didn't want the publicity of Elie receiving the medal and what he might say.

It turns out their plans didn't work out because NBC broadcast Elie's speech live.

-First, give this medal to my son.

[ Camera shutters clicking ] [ Applause ] I am grateful to you for the medal, but this medal is not mine alone.

It belongs to all those who remember what SS killers have done to their victims.

It was given to me by the American people for my writings, teaching and for my testimony.

While I feel responsible for the living, I feel equally responsible to the dead.

Their memory dwells in my memory.

40 years ago, a young man awoke and he found himself an orphan in an orphaned world.

What have I learned in the last 40 years?

Small things.

I learned the perils of language and those of silence.

I learned that in extreme situations, when human lives and dignity are at stake, neutrality is a sin.

It helps the killers, not the victims.

But I've also learned that suffering confers no privileges.

It all depends what one does with it.

And this is why survivors of whom you spoke, Mr.

President, have tried to teach their contemporaries how to build on ruins, how to invent hope in a world that offers none, how to proclaim faith to a generation that has seen it shamed and mutilated.

We believe that memory is the answer.

Perhaps the only answer.

Mr.

President, I wouldn't be the person I am, and you wouldn't respect me for what I am if I were not to tell you also of the sadness that is in my heart for what happened during the last week.

And I am sure that you, too, are sad for the same reasons.

Our tradition commands us "to speak truth to power."

So may I speak to you, Mr.

President, with respect and admiration.

For I know of your commitment to humanity, and therefore I am convinced, as you have told us earlier when we spoke, that you were not aware of the presence of SS graves in the Bitburg cemetery.

Of course you didn't know.

But now we all are aware.

May I, Mr.

President, if it's possible at all, implore you to do something else?

To find a way, to find another way, another site.

That place, Mr.

President, is not your place.

Your place is with the victims of the SS.

We know there are political and strategic reasons.

But this issue, as all issues related to that awesome event, transcends politics and diplomacy.

The issue here is not politics, but good and evil, and we must never confuse them for I have seen the SS at work and I have seen their victims.

But, Mr.

President, I know and I understand we all do, that you seek reconciliation and so do I. So do we.

And I, too, wish to attain truly conciliation with the German people.

I do not believe in collective guilt, nor in collective responsibility.

Only the killers were guilty.

Their sons and daughters are not.

And I believe, Mr.

President, that we can and we must work together with them and with all people.

And we must work to bring peace and understanding to a tormented world that, as you know, is still awaiting redemption.

[ Applause ] -Elie told me that after his speech, Elie thought that he might have convinced Reagan until George Bush came up to him and said, "So you'll -- So you'll go with us."

-Speakes just announced that the president would go to Bergen-Belsen and he will go to Bitburg.

So apparently your plea has not at least immediately been answered.

Does that surprise you?

-No.

I said earlier I'm romantic.

You know, I'm a big romantic.

I thought that since I will make this plea to him, I implore him, that he will get up and say, "Okay."

-You didn't really expect that.

-Mr.

Wiesel, what you did today was really quite extraordinary.

On nationwide television, in effect giving the president something of a moral lecture here.

What were your thoughts about doing that?

-I am not a moralist.

I'm a teacher.

I'm not a politician.

That's my strength.

-You were giving him a lesson.

-No.

I told him a story.

I'm a storyteller.

-He made people think about what they were here for and what was important and what was not.

He was able to translate it into terms that touched people.

[ Indistinct conversations, camera shutters clicking ] -Dear Elie Wiesel, we have been told that you said when your son was born that you felt sorry for him coming into this ugly and evil world.

After a second thought, however, you drew a different conclusion.

Thinking of yourself as a link in a long, long chain of generations.

I think it would be appropriate that your son, with such a precious burden on his shoulders, should follow you up to the podium when you receive the Peace Prize.

[ Applause ] -It was a very, very exciting time.

But everybody reacted differently.

They asked Elisha at the time -- In 1986, he was 14.

They said, "How does it affect you?"

And his answer was, "My allowance will increase."

That's it.

-I had realized as a young person at age 14, that my identity was very much viewed as being in the shadow of my father.

For me, it was just the epitome of everything I didn't want, being known further as just an appendage to my father.

It's 3:35 in the morning on his birthday, 1990.

"Dear Dad, I'm writing this letter at a rather late hour.

I went with a friend to see a hard-core band, the Circle Jerks, play at the Ritz.

The slam dancing was rough and there were some people who got hurt.

Nothing too serious.

All the injuries were unintended.

The dance is a violent one, and these things happen.

I know you don't want to accept any such analogy, but to some extent, I feel it is applicable to us.

We are driven in different directions, as no two dancers can ever be going in the exact same direction.

We both get injured from time to time, even by each other, and yet we both get up a bit dazed and rejoin the dance.

Our love is stronger than the occasional injuries which occur.

I love you always, I miss you.

I never wanted to hurt you and never will, despite whatever I do with my life.

Elisha."

Uh, so here's one that he wrote to me in 1991.

He wrote this in an Israeli bunker as the Scuds were falling during Gulf War one.

And this letter was actually in a sealed envelope at the time that he passed.

My mom discovered it.

These were his sort of last words to me, in case he never got another chance to tell me what was on his mind.

And he says, "My dear Elisha, if you promise not to be angry, I will tell you something: I love you.

Should anything happen to me in Israel, I hope you will remember at least some of the things I tried to share with you.

Remember my father, after whom you have been named."

"Remember that you are a Jew.

Remember that even within the doubt, there is a God, the God of Israel.

Take care of yourself.

You have been and remain the center of my life.

With infinite love, your father."

-For Elisha and for me as well, having babies has been that process of coming back to ourselves and our centers and our our upbringings, our...faith.

-What memories do you have of your grandfather?

-Okay.

I remember in his study when I was little, he -- Every morning, he and I would both wake up early.

And in the mornings, he'd go up to his study and he'd put on his tefillin, and I would just stand outside his study, opening and closing the doors.

-Sometimes it feels like there's so much pressure on me to be like my dad and my grandpa.

-I definitely agree.

Um, I... -Wow.

-Wow.

So... -100%.

-The two things Elie asked of Elisha were that he marry a Jewish woman and that he recite Kaddish after he passed.

So Elisha did just that.

But somewhere in that journey, Elisha realized it was a gift for himself.

And then gradually Elisha started to reintroduce more tradition into our lives, into his life, and really did a deep dive into Judaism.

-So are you ready for a quick one?

-Chess?

Alright.

-Okay, baby.

Oh!

-I like the Grand Prix variation.

-Oh.

-That's a latke?

-Yes.

-Doesn't look like a latke.

-I know, but your son made it.

-Really?

You're blaming it on me now?

[ Laughter ] I told Anne that it was your final test before dad would marry you, that you had to make a latke.

-He wouldn't have married me, you wouldn't exist.

-If it was -- If this was the latke.

-Yeah.

-It's time to light the candles.

-♪ Baruch atah Adonai ♪ -I've always been a little afraid of religion of any kind.

I know that I was always afraid of anything that compromised one's will and relegated it to an inferior position to something else, which was religion.

So I was a pagan in the family.

-My faith is a wounded faith.

But it's not without faith.

My life is not without faith.

I didn't divorce God.

-What I think was special about him was that he saw the trauma as something that has to lead to moral action.

-I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation.

Human suffering anywhere concerns men and women everywhere.

And in spite of what some extreme critics have said about me, that principle applies in my life also to the Palestinians, to whose plight I am sensitive, but whose methods I deplore when they lead to violence.

Violence is not the answer.

Both the Jewish people and the Palestinian people have lost too many sons and shed too much blood.

This must stop.

-He didn't want to criticize Israel under any circumstance.

He didn't want to criticize the occupation.

He didn't want to criticize the settlers.

He may not have agreed with them, but he didn't want to criticize them...ever.

-And we have learned that when people suffer, we cannot remain indifferent.

And, Mr.

President, I cannot not tell you something.

I have been in the former Yugoslavia last fall.

I cannot sleep since.

We must do something to stop the bloodshed in that country.

[ Cheers and applause ] -The number-one lesson that I learned from him was your suffering...is not what defines you, but it informs you.

It can shape you, and then it's your job to make it the best tool that you can.

-If you had to summarize the greatest offering that you've been able to give your students, what would that be?

-I came up with a formula.

I'm not sure it's always good, but I said simply, look, whatever you do in life, remember, think higher and feel deeper.

-The last day of a semester, a student asked Professor Wiesel, "Professor, can you show us the number on your arm?"

And there was dead silence in the room, and without a word, he took off his jacket and rolled up his sleeve and showed the number on his arm to the class.

There were about 65 or 70 students in the class.

And in silence, he rolled his sleeve back down and buttoned it and put his jacket back on and said, "Next question."

-I do not believe that there are, that there could be, or even there should be novels about the Holocaust.

Either a novel is a novel or it is not.

And when it is about the Holocaust, it is not.

-He developed very strong relationships with all of his students.

I saw them being transformed.

-Part of what we had to do each semester was you would choose a book from the -- the list of texts that you're reading and you would present.

You would give a little wee presentation on the book, you know, that week.

And everybody was always super nervous about it.

-When I got up to give the presentation and I was talking about this character who had very dark skin and those things, I realized how much it, like, affected me.

And in the moment that it was in the class, I broke out into tears.

Because that space was open to talk about memory, right, and to talk about things like trauma, people were open.

-Remember the enemy.

And that is an attitude which is a very strong attitude.

Imagine the victim simply saying to the torturer, "Look, you can do whatever you want, but I will remember you."

This is what frightens the enemy most usually.

Nothing frightens enemy more.

To be vanquished, okay.

Vanquished today.

Come back tomorrow.

But the idea that the victim will remember the enemy, the memory will remain, that is the real punishment.

-Memory is what makes us civilized.

You know, like, that is what makes us human.

And "never again" means something to me.

Right?

It's -- That is that I have a responsibility that goes beyond myself and my beliefs, and that I'm a part of this... global community.

-I grew up in the very southwest part of Germany.

And all my classmates and myself were very much interested in political questions.

One day I met somebody and he said, "Read the book 'Night' by Elie Wiesel."

I couldn't manage more than one or two pages a day because it moved me so much.

[ Speaking German ] -[ Speaking German ] -The fact that Elie said, "I'm not going to be silent."

And so much of my life, people tell you, this tall, dark-skinned Black man, to shut up.

That what you have to say is not that important.

Who you are is not important.

And that 100-page book says, "No, I got a story."

-The commentary in the Talmud is, if you are my witnesses, I am God.

If you are not, I am not.

My God, my God, I want to say, no, really.

To say that and to accept it as part of belief, I give up.

Which means, what Heschel said, you know, God in quest of man, in search of man.

You need -- God needs human beings, us, little specks of dust, to be God.

The mystical teaching tells us that it is possible for any person to bring the Messiah to the whole world.

And I believed it.

I no longer believe it.

I believe today that it is possible for you or me or anyone to bring a moment, a messianic moment, to each other.

If I could simply bring a messianic moment into the life of one person, I think that my life would have been justified.

"Night" is, to me, of course, a very special book.

It is the basis for all the other books, the foundation.

-Good afternoon, good afternoon.

Good afternoon.

-I'm gonna start chapter one of "Night" by Elie Wiesel.

We're gonna learn about Elie's family and sort of his introduction to Judaism, like, who he is as a person.

And we're gonna slowly transition into this, like, ominous mood of the Holocaust sort of brewing in the background.

Let's open up to chapter one.

This is our five to six weeks to really focus on, um, Elie Wiesel.

"I met him in 1941.

I was almost 13 and deeply observant."

Raise your hand if you're 13 in here.

Look at you.

So in a lot of ways, this is a story that could relate to us.

Let's keep going.

Kids know that 6 million people who were Jewish died and were killed.

And so they have some context about, like, how Hitler came to power.

Um, they have some context about what it means to practice Judaism, um, and some general ideas about what the world was going through around World War II.

-Regular, normal Germans that were sophisticated and intelligent, they conformed with Hitler.

-6 million Jews were murdered because of the fact that they were deemed as "genetically inferior," due to the fact that maybe they weren't fully German or that they had disabilities.

-How is a mood of being in the ghettos different from the mood of children playing in the street?

How did the mood change in ghettos?

-Back then, ghettos also described something negative that still -- they still mean something negative to this day.

-They're really trying to see, "Are we similar to Wiesel?

Would we react in that way?

Can we imagine it?"

Most of us cannot.

How did normal people get to this point where a tragedy like this could happen?

-The Nazi, they controlled everything.

Everybody hearing the same thing all at the same time.

So if everybody hears the same thing all at the same time, they would all think, "Oh, since he's doing it, I should do it."

-People were ignorant to the idea that they were just killing innocent people that they didn't know.

-Most of our students are from Newark, live in Newark.

They come from backgrounds that are not... They've never experienced anything like the Holocaust, but the context of sort of underbrewing tones of violence, in a lot of ways, the undertones are similar.

...beliefs in God.

How does his relationship with his father shift?

-He's probably gonna be feeling anger for being, like, having to take care of his father at 16 in a situation like this.

-I feel like everything bad that happened made Wiesel stronger, since now he has to care for his father.

-I kind of disagree when Isabelle said that made him stronger in the end, that he was still broken down emotionally.

-This is dehumanization because one of the main things that makes a human human is them having the right and the ability to choose.

-I feel like freedom is being able to choose life or death.

And I feel like freedom is being able to have an option.

And I feel like you cannot define freedom.

So people define freedom for themselves.

-God hasn't given up on Elie yet, but Elie is trying to give up on God.

But God is still giving him chances and still letting him survive.

-It's not God.

I feel like it's more like fate.

-I feel as if God didn't create the Holocaust.

Because I feel as if he gives us a choice to choose.

So it wasn't really his fault that the Holocaust happened.

-Maybe God is putting him through this to make him understand that... that God is just not... not just there to make you happy.

God is there to just lead you through life in general.

-What was the most impactful part of the book for you?

-The most impactful part was when his father died.

-This is powerful to me because this is, like, a different situation.

And I don't know what to expect because I've never experienced it.

But I feel like if I did and I had to let go of my mom, I don't even know what I would do with myself.

-I feel as if when he wrote this book, he was trying to let go of his pain, so he won't have to feel the pain of having to relive those moments over and over and over again.

-This isn't the same world Wiesel was in when he was younger, because we even see that change in his name.

Throughout the book he's called Eliezer.

But as an author, and when we're talking about him in a present tense before he passed, we say, Elie.

That just shows that he's now in a different world.

So even though Elie is free, Eliezer was never freed from his past.

Elie Wiesel is free.

Eliezer is not.

-I love you.

-I love you, too.

I'll, uh, I'll see you in eight days.

-Why is it that my town still enchants me so?

Is it because in my memory, it is entangled with my childhood?

Evil remains hidden and time suspended.

In my fantasy, I still see myself in it.

-In a tiny place like Sighet, until 1944, people lived together.

Hungarian Gendarmerie was here, present all the time.

They even lived in Jewish homes.

And suddenly, overnight, they became the perpetrators.

-I saw them with their bundles on their shoulders.

The Hungarian gendarmes were driving them mad with fear.

My sisters and myself, we went to the well and brought them water.

Then three days later, I was myself among them.

Still am.

-Are most of the people who visit Sighet as tourists aware of the Jewish history, or do they just come here because... -Most of them are not.

-Yeah.

-Most of them are not.

I would say that, um, 90% of them are amazed that Sighet was actually a Jewish town.

-Mm-hmm.

-Everything is the same -- furniture, even the wallpaper, and it is so much the same... that, at times, I'm afraid... that perhaps the door might open and the young boy that used to look like me will come out, and he will ask me very innocently, "Tell me, what are you doing here, stranger?

What are you doing in my dream, in my tale?"

-We're looking for Eliezer, right?

Because your grandfather was -- was named after his grandfather.

-Where?

-This one is here.

-That's a... -Benyamin.

It's Yehuda Benyamin, you see?

-This is the wrong one, then.

-Yeah, it's not this one.

Oh.

-Possibly?

-I think that's a mem.

-Oh, wait.

-Eliezer.

-Oh, that is a lama.

-Eliezer.

This is Eliezer.

Yes.

-Okay.

-Ben.

-It should be Ben.

-[ Speaks Hebrew ] Shalom haLevi.

This is i-- Yeah, this is it.

We found it.

This is my great great grandfather, Eliezer Lazar Wiesel haLevi.

Oh, wow.

Rav Eliezer Wiesel.

It's a -- I've never seen it spelled like that, but that's how it's pronounced.

-"I visited all the places which had once filled my landscape.

I searched for the people out of my past, but I did not find them.

The only place where I felt at home was the Jewish cemetery.

This was the only place in Sighet that reminded me of Sighet.

I wandered from one grave to another.

I had bought some candles.

I lit them, placing one wherever I found a familiar name.

The wind blew them out and suddenly tears strangled me.

A terrible certainty overcame me.

For the town that had once been mine never was."

-My hometown was only famous for the concentration camp Sachsenhausen.

Unfortunately, there were no Jews left.

"They came first for the communists.

And I didn't speak up because I wasn't a communist.

Then they came for the Jews.

And I didn't speak up because I wasn't a Jew.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a trade unionist.

Then they came for me, and by that time, no one was left to speak up."

I learned that Elie Wiesel had a type of blood cancer.

[ Horn honks] He was sent to us to participate in a clinical trial with a drug we have never used before.

Hello, Dr.

Lentzch speaking.

I had a phone call with his son, Elisha, and talking to him for the first time wasn't that easy.

Giving the life of his father into hands of a German doctor, a drug that has never been tested in New York.

He said if there is a chance and if we have an option, even if it is an experimental treatment, maybe we give it a chance.

But the final decision has to be made by my father.

Elie Wiesel responded very nicely, but after a year, the treatment stopped working.

Elisha said, "If there's nothing else we can do, then I want to take him home."

-I remember in the moments after my father passed, there was this -- this rush, um, like my blood rushing in my head.

I had to sit down because... there was this voice in my head saying that my father hadn't gone anywhere, that he was with me and always would be.

-I believe that life does not end with death.

I feel the presence of my father all the time.

The same is, of course, with my mother and my little sister.

I feel their presence, which means their death had their own presence.

It's up for me to accept it, and I do.

It doesn't mean that I don't believe, but I don't know.

But between belief and knowledge, there is an abyss.

But what would one be without the other?

[ Singing in Hebrew ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Behind the Scenes of Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/28/2026 | 5m 38s | A behind-the-scenes look at the making of Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire. (5m 38s)

Elie Wiesel on Palestine, trauma and suffering

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2026 | 2m 21s | Elie Wiesel vowed to always speak up whenever people were enduring suffering and humiliation. (2m 21s)

Elie Wiesel recounts the horrors of the Holocaust in "Night"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2026 | 1m 56s | In "Night," Elie Wiesel recounts a memory of witnessing three victims being hung. (1m 56s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 1/27/2026 | 2m 9s | Learn about Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author of Night. (2m 9s)

Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire [ASL]

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 1/27/2026 | 2m 9s | Learn about Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author of Night. (2m 9s)

Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire [Extended Audio Description + OC]

Preview: 1/27/2026 | 2m 43s | Learn about Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author of Night. (2m 43s)

How Elie Wiesel's wife and son gave him a new lease on life

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2026 | 2m 40s | Before meeting his wife Marion, Elie Wiesel "shunned love" and didn't see himself having children. (2m 40s)

How Elie Wiesel was reunited with his sister

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/27/2026 | 1m 10s | Elie Wiesel reunited with his sister in France. (1m 10s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Support for American Masters is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, AARP, Rosalind P. Walter Foundation, Judith and Burton Resnick, Blanche and Hayward Cirker Charitable Lead Annuity Trust, Koo...

![Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire [ASL]](https://image.pbs.org/video-assets/1HkDWrj-asset-mezzanine-16x9-k3i9SRf.jpg?format=avif&resize=316x177)

![Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire [Extended Audio Description + OC]](https://image.pbs.org/video-assets/ybrtuZy-asset-mezzanine-16x9-QzrBo71.jpg?format=avif&resize=316x177)